Photographic research

is based on obtaining as much information as possible about an image,

then building a logical context for a possible identification of the

image. As new information is located, it is compared, and the interpretations

checked for "fit" given the new data. This context can be

in the form of:

Evidence

- objective, factual, documentary information provided by the photograph

or its context (e.g. format, content within the photograph, attribution

to photographic studio based on imprint or printed identification

from the period, etc.)

Interpretation

-building on circumstantial evidence and context that can be clearly

verified to and by others (e.g. dating from format or image content,

verification of period or more recent written identification, comparison

with other known images, etc.)

Speculation -"Leaps of Faith" based on attribution by

later generations, hearsay creative interpretation or desire.

Each can provide valuable

information that must be evaluated and verified before it can be relied

upon. For example, evidence such as photographers imprints can often be

incorrect for copied images, a common photographic practice since the birth

of photography through the era of Kaloma in 1914. For example, the well-known

images of Geronimo by Irwin, Randall and Wittick, and C. S. Fly were frequently

copied and today examples regularly appear with imprints of many other photographers.

Interpretation based

on the format of the photograph or information within the image, such

as building signs, can help verify or refute written identification that

may have been added to the mount. All written information associated with

an image should be confirmed, particularly if it was added after the image

was originally produced. Well-intentioned family members, collectors and

museum staff often add attributions to the photographs that pass through

their hands. Their impressions or knowledge, and the accuracy of the written

information, should be verified before it is assumed to be correct.

Speculation may be

based on interpretation of available evidence, on emotional reaction to

a photograph, or desire to "trim"a piece of the puzzle of history

to make it fit. Speculation can be benign or unintentional when it is

based on little knowledge or incorrect information. Personal desire or

a potentially escalating image market can also drive speculative interpretations.

For example, a tintype photo showing a young man in a bowler hat is found

in an old family album. A quick search locates photos of young Butch Cassidy

in a bowler hat from this era. If there is some similarity to build and

facial features, an uninformed or unscrupulous seller could conclude that

the tintype is of Butch Cassidy and promote the photograph as a new unknown

Butch Cassidy image.

Every photographic

identification is only as accurate as the weakest link in the information

about the image available at a given time. Anecdotes and speculation make

great stories but are merely weak links in accurately identifying a photograph.

Unfortunately, once

incorrect information becomes widely available through print or the web,

it can be extremely difficult to rein in the error and replace it with

correct information. For many years the Smithsonian recommended cleaning

daguerreotypes with thyrea, a chemical found in silver cleaner. In the

1980s research showed that thyrea damaged the plate and should not be

used. Many collectors and antique dealers still find old references by

sources highly credible when originally published, and use thyrea to clean

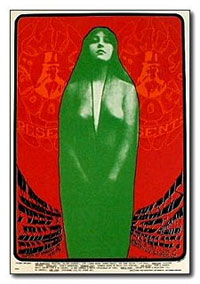

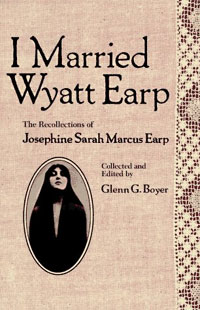

and damage their valuable images. The image of Kaloma has taken on a life

of her own through Boyer's book cover and the trail of auction catalog

descriptions that built upon his attribution.

Images of towns or

events often include building signage or other information that simplifies

identification. Questions about the date and location of unattributed

images of family members or unknown individuals are common in photographic

research and genealogy. Unfortunately, portraits rarely include such helpful

clues, making identifying anonymous portraits extremely difficult.

Many individuals

share common facial features, and even radically different faces can look

similar when viewed from certain angles. For this reason, most museum

staff, knowledgeable researchers and collectors require provenance or

history about the image to support physical similarities that might exist.

Rarely will they weigh in with tentative identifications of new or unique

images of famous people based only on visual similarities with other known

images. Tentative identification of images thought to be Emily Dickinson,

Abraham Lincoln, and Jesse James based on perceived similarities are among

many that are currently being disputed by museums and collectors, and

in the press.

Looking at context

and dating clues in the photograph is a good start at going beyond perceived

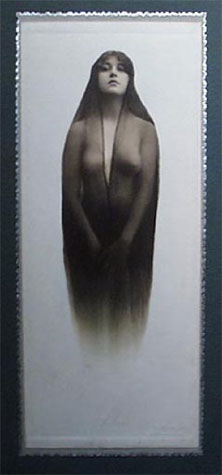

physical similarities. Most of the early Kaloma images seen to date are

photogravures. These high quality reproductions from photographs were

produced from engraving plates on a printing press, and were much less

costly for publication runs than actual photographs. Photogravures were

often printed with title and publication data below the image and were

commonly used to create many copies of high quality illustrations for

books, postcards and art magazines. Though photogravures had been used

since the 1850s, their surge in popularity was between 1890 and 1920.

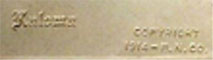

Copyright notifications

have been printed on photograph mounts and occasionally in the image area

since the 1850s. Notices were occasionally printed or etched in the negative,

or later added to the surface of the print with a rubber stamp (C. S.

Fly used stamped copyright notifications on many of his images of General

George Crook and the surrender of Crook and Geronimo). Though copying

and piracy were common, pirates rarely included previous notices when

illegally reproduced. The Kaloma images seen to date have all been associated

with copyright notices dating from after 1914. The photograph on the sheet

music is unattributed, though the music is copyrighted to Cosmopolitan

Publishing Company.

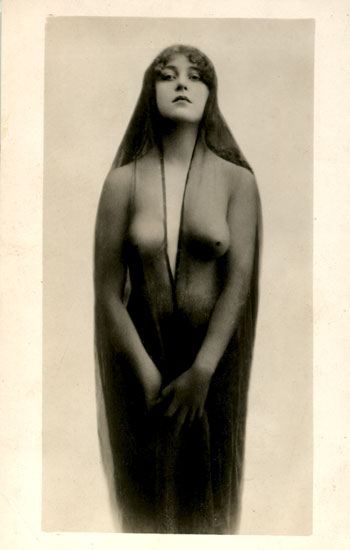

Risqué photographs

like the Kaloma image have been made and sold since the 1840s. These images

rarely included photographer's credits or copyright notices. Also, the

subjects of such "art"photographs were not usually identified.

It is highly unlikely that even if the subject of Kaloma had been identified

at some point, such documentation by photographer or publisher would still

exist. However, given the heated levels of discussion about the current

attributions, and possible liability given Kaloma's high recent sales

prices, it is not likely that publishers or distributors will actively

take sides in this matter. Obviously locating documentation of the sitter

of the Kaloma image will be key to unraveling the controversy about this

image.

During much of their

lives, the Earps were popular, widely known, public personalities. Though

few commercial portraits of the Earps exist, if images were available

at the time it is likely that they would have had a large and ready market.

Prints were relatively affordable with individual cabinet card portraits

costing about $1.25 per dozen, and group portraits slightly more expensive

at about $1.50 per dozen.

The C. S. Fly studio

in Tombstone was known for its marketing. Thousands of copies of images

of the surrender of Geronimo were printed and sold. Similarly, portraits

of personalities visiting Tombstone, and photographs of local events like

the hanging of John Heath, were broadly distributed. If as speculated,

Fly took a salable image of Josie Earp, it is highly unlikely that he

would not have capitalized on the opportunity to sell copies. To date,

no copies of the Kaloma image have been located on Fly studio mounts.

Photographic styles

changed regularly every few years as photographers sought to justify new

portrait business, and as lenses, formats and emulsions continually evolved.

By looking at large numbers of images it is possible to get a feel for

the photographic style from a given era. Images that don't fit the norm

exist, and are often highly valued by collectors as precursors of future

styles and trends. However, it is safe to say that most images tend to

fit the stylistic trends of their era.

The Kaloma image

has three strong stylistic elements that can be used to try to assign

a range of dates to the original photographic image.

- The

sultry interaction between the subject in Kaloma and the photographer

is very direct. This style is more common and representative of risqué

images and nude studies from the post card era (1905 1920) than earlier

19th century images.

- The full figure

vignetting of the image is stylistically more common during the post

card era than earlier. However, earlier images were reprinted in current

formats years after they were originally taken. It is possible that

Kaloma was printed from an older negative and vignetted to be stylish.

- The

use of narrow depth of field (the range of sharp focus in the photograph)

was popularized by art photographers in England and Europe in the late

1880s and in America around the turn of the century. However, the number

of photographers using this technique was only a small fraction of commercial

photographers. Aesthetically, the Kaloma image shares much more with

post 1900 images than earlier images.

In short, at this

point there is little evidence, some interpretation from that evidence,

and much speculation about the subject of the image known as Kaloma. Looking

at the image and trying to read the story it tells leads logically to

an early 20th century photograph of a beautiful young woman,

likely taken after about 1910, that first burst on the scene in 1914.

No clues clearly indicate this image was copied from an earlier image

of Josie Earp or another as yet unidentified young woman.

Though a few large dollar sales continue, including a sale of $2,750

at Wes Cowan’s Historic Americana Auction on November 15, 2001, Kaloma

seems to be settling down a bit as logic and reason begin to impact the

market. As this is written, several online sales citing the Josie tie

to Kaloma have dropped to under $1,000. Several have sold on eBay, including

a copy that realized $900 on February 24, 2002. Online offerings above

that figure seem to languish both at auction and at dealer sites. One

eBay posting of Kaloma that closed on June 16 only reached $152.50 and

did not reach the reserve. Another closed on June 25 selling for $950

against an estimate of $800 – $1200.

Given the broad exposure

that the image of Kaloma has had over the past 26 years and strong interest

the legends of Tombstone, researchers will continue to search for compelling

evidence to link this image with Josie Earp. In the meantime, without

any strong objective evidence to support the claim that Kaloma is an image

of Josie Earp, this identification will unfortunately be based only on

speculation.

|